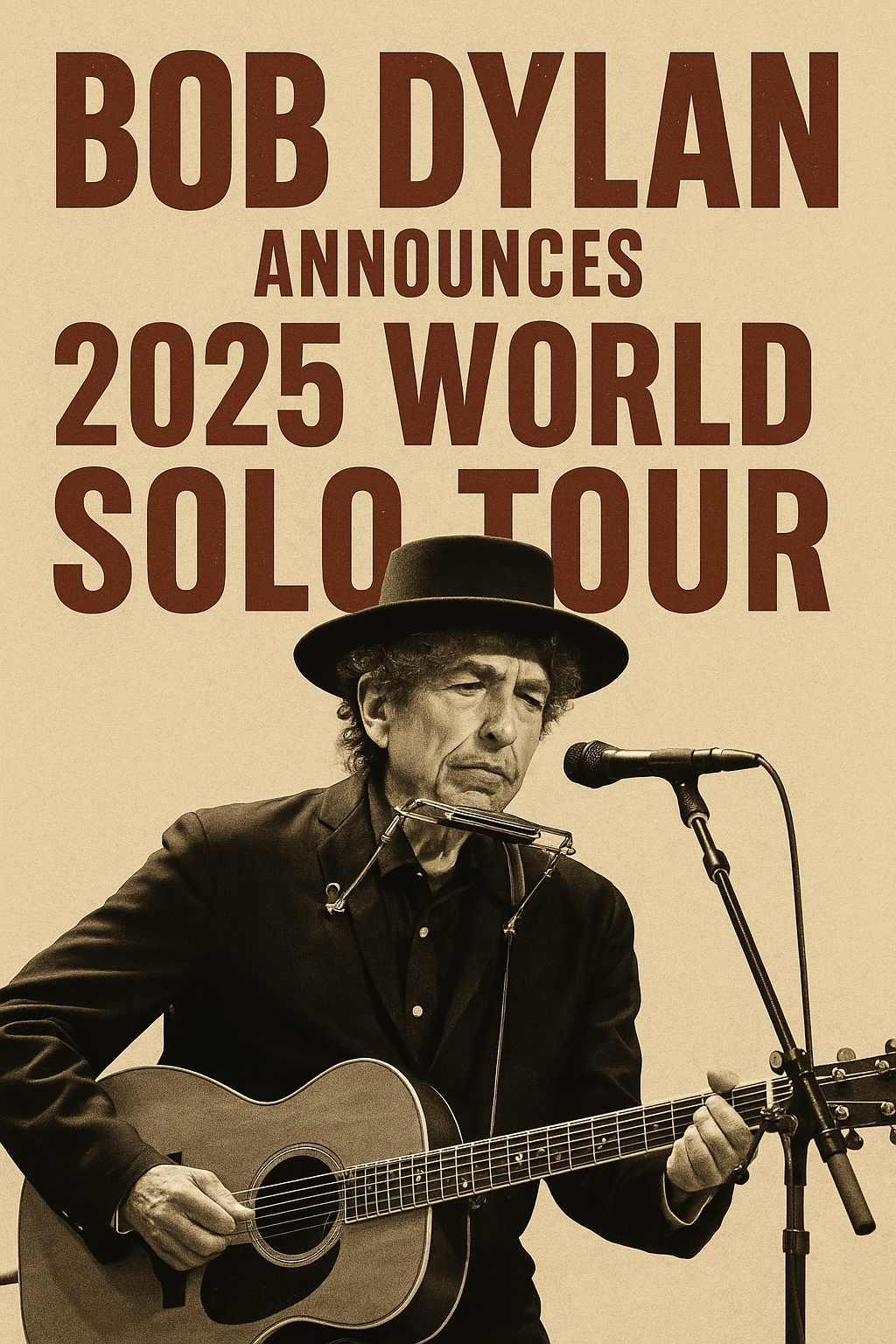

Bob Dylan’s Masterpiece: “Desolation Row” and the Anatomy of American Apocalypse

Bob Dylan has written many songs that have shaped the cultural and political landscape of modern America, but few carry the mythic and surreal weight of “Desolation Row.” The final track of his 1965 album Highway 61 Revisited, this eleven-minute epic has become more than just a song—it is a poetic autopsy of the American dream, a surrealist canvas smeared with fading ideals, historical shadows, and prophetic dread. In “Desolation Row,” Dylan holds a cracked mirror to the American psyche, and what stares back is haunting, beautiful, and terrifying.

A Parade of Broken Icons

From the first eerie guitar notes, Dylan plunges the listener into a chaotic carnival of characters. T.S. Eliot argues with Ezra Pound. Ophelia is trapped in a postmodern nightmare. Einstein is disguised as Robin Hood. Biblical figures, Shakespearean characters, and American legends all make their ghostly appearances, but none of them are whole. Each figure is stripped of their original meaning, lost in a dreamscape of cultural decay.

Dylan isn’t simply showing off literary references—he’s weaponizing them. These distorted icons are no longer symbols of greatness, but warnings. They speak not of glory, but of collapse. This isn’t just a song; it’s a dismantling of America’s mythology.

Apocalypse in Slow Motion

The apocalypse of “Desolation Row” is not the sudden, fiery end of civilization. It is far slower and more insidious. It is a spiritual rot, a crumbling of the soul masked by circuses and distractions. Dylan’s vision is not of bombs falling, but of values eroding and truth vanishing in plain sight. “They’re selling postcards of the hanging,” he sings in the first line—a sickening metaphor for how horror becomes commodity in a society too numb to care.

Every verse piles on more evidence of this disintegration: the cynicism of institutions, the impotence of intellect, the despair of beauty lost in madness. Dylan is not ranting—he is observing, painting, and damning with every brushstroke.

Music as Prophecy

Musically, “Desolation Row” defies pop conventions. It meanders, it meditates, and it refuses to be boxed in. The fingerpicked guitar, played by Nashville session guitarist Charlie McCoy, lends it an intimate, almost ancient sound, like a bard singing at the end of time. There is no chorus, no release—only the steady unfolding of Dylan’s lyrical nightmare.

But that is the genius of the song. It is less interested in being catchy than in being eternal. It predicts a society of fractured attention, where chaos is normalized and meaning is drowned in noise. In that sense, “Desolation Row” was not just about 1965—it was prophetic. Its vision of a disoriented world, spinning toward oblivion, feels frighteningly contemporary.

The Road to Nowhere

Ultimately, “Desolation Row” is not just a location. It is a state of mind, a metaphorical street corner where disillusionment gathers like fog. We are all, Dylan seems to suggest, a little closer to it than we’d like to admit.

The masterpiece doesn’t offer answers. It doesn’t point to salvation. But it forces us to look—really look—at where we are headed. And in doing so, it secures Dylan’s place not just as a songwriter, but as a prophet of America’s fragile soul.

“Desolation Row” isn’t a song you just hear. It’s a song you enter. And once you’re inside, you don’t come out the same.